Joe Banks excavates the layers of ideas and associations buried within his video installation ‘Ammonite’.

“Fossils fascinate me – they’re like time capsules; if only one could unwind this spiral it would probably play back to us a picture of all the landscapes it’s ever seen” – J.G. Ballard, Prisoner of the Coral Deep, 1964

Ammonite is a 15 minute long “video organism”, created using standard definition domestic TV and video equipment, in conjunction with a 632.8nm helium-neon research laser. Ammonite uses laboratory optical and digital film techniques to create a minutely-tuned and hypnotic visual feedback loop – a kinetic artwork, in which emergent form self-organises into the image of a gently pulsing and apparently living organism. The installation appears, at first glance, to be filmed in black-and-white, but is in fact realised in colour. The artwork was created in July 2009 and first exhibited in January 2010.

As the title suggests, the video resembles the coiled and (in fact) moving forms of the extinct marine Ammonoidea – shell-bearing cephalopod molluscs, the relatives of modern “ink fish”, of octopus, squid and cuttlefish, which evolved during the Devonian geological period, approximately 400 million years ago. The video also resembles, to an extent, the growth patterns and geometry of ferns – primordial species which also emerged during the (late) Devonian period.

In terms of the history of contemporary video art, Ammonite is a genre-piece, and can, to an extent, be considered to be an affectionate parody of early video art, as versions of the technique used to create this exhibit have been used by artists as far back as the title sequence for the TV series Doctor Who, broadcast in 1963 (see here and here). As such, the technique used to realise this work is extremely simple, however Ammonite remains unique among video feedback artworks – first, considered as a work of visual music, on account of the sheer delicacy and the sustained precision of this system’s manual tuning, and second, in being a work of representational (as opposed to abstract) art. In terms of musical analogies, the system itself is a form of optical and kinetic oscillator. Adapting the language of molecular biology, the video can be presented as complementary, mirror-image “Sense” and “Anti-Sense” versions, displayed together using two standard-definition broadcast monitors. The specific camera used to generate this sequence is notable for featuring a night-vision system that is popular among paranormal researchers.

Charles Darwin, the father of evolutionary science, argued that morphology – the comparative study of shapes and forms – is the “very soul” of natural history 1; William Bateson, the inventor of the term “genetics”, stated that “a living thing is not matter” but a “vortex through which matter passes”2; and, as I’ve previously stated, “art is not necessarily science, but science is always art”34. The spiral flows outwards, and draws in the viewer, the growth of the spiral is both a direct form of and a metaphor for evolution, just as artistic creativity is in itself a metaphor for the creativity of the natural world. As the name “Devonian” implies, this period in the evolutionary time-scale takes its name from the county in whose landscape rocks identified as coming from the period were first identified, and this etymology also serves to remind us that the video in question is a not only an electronic genre piece but also a work of landscape art.

Considering these ideas and this imagery in terms of visual perception, it’s relevant to observe that in his pioneering essay “Meanings of Landscape” the curator and naturalist Geoffrey Grigson proposed the notion that “landscape is you and me”, discussing how “we project ourselves” into an actual or painted landscape, “which then reflects our own being back to our eyes”5. In his commentary for the book The Living Rocks, Geoffrey Grigson described fossils in general as “images of life”, and ammonites in particular as “a ghost in stone”6. In terms of suggesting how such imagery can be perceived through the medium of television, it’s relevant to point out that, parodying the famous aphorisms of the media theorist and philosopher Marshall McLuhan, the film-maker David Cronenberg wrote, in the scripted dialogue for the movie Videodrome (released 1983), that “the television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye”, so that “whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it”7.

With a nod to the poem of the same name by Geoffrey Grigson, the Ammonite video experiments with novel techniques for the representation of natural objects – of real fossilised ammonites, which emerge from the physical landscape, falling from inland and coastal cliffs, found in rivers and streams, and dug from quarries and chalk pits etc. The philosopher C.W. Morris defined semiotics as “the science of signs”, and, in addition to the figurative resemblance, in terms of visual semiotics, the analogue monitors and “distressed” source DVDs used to exhibit the Ammonite video are also re-used, faults intact, so that artefacts of colour-cast and visible glitching etc act as visual signifiers, reinforcing the impression, in this context, that even an electronic medium like video is also an organic and in some respects almost living medium. Likewise, the medium combines with its own (visual) message (with its own visual content), to suggest and reinforce an equivalent notion – the idea that living systems can be understood to be forms of machine.

As regards visual semiotics and cultural symbolism, in addition to the types of visual readings and resonances already discussed, fossilised ammonites or “shaligrams” are regarded in Hindu culture as naturally occurring signs, as anthropomorphic “murtis” or images of the Gods, in fact as direct manifestations of the Hindu deity Vishnu. An equivalent reading in Western visual culture is the interpretation of ammonites as being the petrified remains of coiled snakes, associated for instance with the mythology of Saint Hilda, of Whitby, near Scarborough, and Saint Patrick, the primary Patron Saint of Ireland (who banished snakes from Ireland by turning them to stone).

On a more prosaically technical but also fantastical level, the Ammonite video strongly resembles features of the geometric figure discovered by the mathematician and communications theorist Benoit Mandelbrot – the phenomenally complex and intimidating Mandelbrot Set, the most complex object in theoretical mathematics – suggesting that the system created to make this video expresses a form of fractal geometry. Finally, returning again to the history of cinema, further examples of related imagery can be seen in the extraordinary movie Uzumaki (released 2000) by the artist and film-maker Akihiro Higuchi (aka Higukinski), which is based on the manga of the same name, illustrated by the artist Junji Ito. In the film Uzumaki an entire landscape is infested with malevolent spirals, and the spiral is celebrated, in dramatically obsessive and macabre terms, as “the highest form of art”.

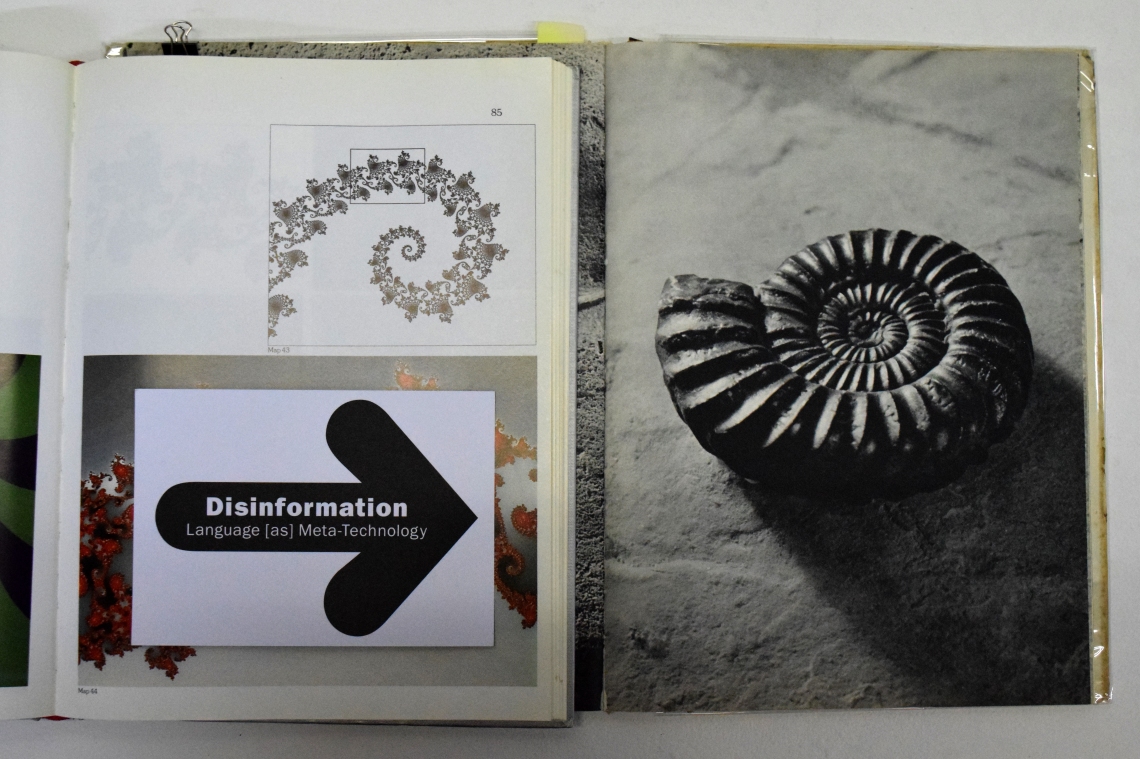

The photograph above features a selection of reference material displayed during the “Language [as] Meta-Technology” exhibition at Sluice HQ, London, November 2018. The information desk set-up during the exhibition featured the books The Living Rocks, with photographs by Stévan Célébonovic, a preface by André Maurois, and commentary by Geoffrey Grigson (Phoenix House 1957), and The Beauty of Fractals: Images of Complex Dynamical Systems by Heinz-Otto Peitgen and Peter Richter (Springer 1986). During the International Lawns, Disinformation and Rural College of Art exhibition at the White Box Gallery, London, July 2019, the Ammonite video was exhibited alongside the poem “Ammonite, Under Sun and Thyme”, as it appears in The Collected Poems of Geoffrey Grigson (Phoenix House 1963) and in Geoffrey Grigson: Selected Poems edited by John Greening (Greenwich Exchange 2017).

Ammonite, under Sun and Thyme

Marjoram, rockrose, thyme,

Pun of scent and clock;

An ammonite concerns me

Half in the rock.

Half shown by thyme

In zebra’d form

Happens to be today

Shadowed, warm.

Where it was, when,

How it swam, in which sea

Are concerns not much

Attracting me.

It occupies space, is in

Time, I’m aware,

Glad that it should,

Like myself, be here.

Geoffrey Grigson, Collected Poems, 1963

Ammonite at Dronica Festival, documentation:

Ammonite video – 768×576 4×3 DV colour PAL, 15 minutes [single or split-screen, silent] – installation © Disinformation 2009. Artwork realised by Joe Banks, with special thanks to Barry Hale.

–

1 – Charles Darwin, On The Origin of Species, John Murray, 1859 (quoted in “The Rumble” exhibition catalogue, Royal Society of British Sculptors, March 2001).

2 – Adam Lowe & Simon Schaffer, “Noise” exhibition catalogue, Kettle’s Yard Gallery, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

3 – Joe Banks, “The Rumble” exhibition catalogue, Royal Society of British Sculptors, March 2001.

4 – Joe Banks, “Rorschach Audio – Art & Illusion for Sound”, Disinformation 2012.

5 – Geoffrey Grigson ,“Meanings of Landscape” in Places of the Mind, RKP, 1949.

6 – Stévan Célébonovic, André Maurois & Geoffrey Grigson, The Living Rocks, Phoenix House, 1957.

7 – David Cronenberg & Jack Martin, Videodrome, New English Library, 1983.

Click for more articles in this issue: