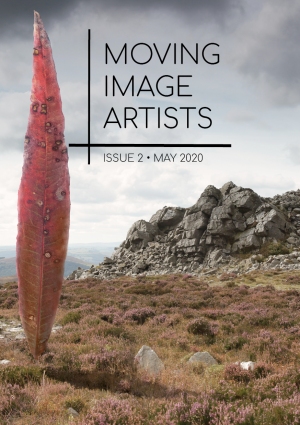

Yvonne Salmon and James Riley gather research and reflections on their expanded cinema project ‘Headlands’.

Landscapes of Dream. Various landscapes pre-occupied Talbert during this period […] In these landscapes lay a key.1

I

The Headlands Hotel is in Port Isaac, North Cornwall.2

A fine prospect.

Up there on the hill it commands the best view of the bay. Room, board and a base for the week.

Spend the first day sitting by the window and you’ll feel the gentle pull of the tide. You’ll also see just how many people walk up here with cameras. Backs to the sea, they take photographs of other people enjoying the view.

Understandable.

The sea dominates.

It’s too much, this place of the old baptism. The dogs bark at it. By the second day you’ll be keeping a dream diary. The tidal rhythms pushing at the open window will have sent a ripple through your alpha waves.

Take note: Headlands is a house of troubled sleepers.3

II

In 1981, the Cornish village of Port Isaac was used by the BBC as the primary location for their shot-on-video serial The Nightmare Man. Based on David Wiltshire’s novel Child of Vodyanoi (1978) and produced by the creative team behind Doctor Who, The Nightmare Man was a story of UFOs and experimental flight technology.4 It combined cold-war paranoia and pulp science fiction with European myth and haunting shots of the English coastline.

In 1645, Anne Jefferies went to work as a maid for the Pitt family in St. Teath, a hamlet just inland from Port Isaac. Soon after her employment began, Jefferies was found in a state of disorientation at the gate of the Pitt house. As Moses Pitt would describe in a 1696 letter to the Bishop of Gloucester, Jefferies recovered from her ‘fit of convulsion,’ reporting that she had met and travelled with ‘airy people, called fairies’.5 Some Ufologists, particularly Jenny Randles and Chris Aubeck, have presented this letter as one of England’s earliest accounts of a ‘fourth kind’ or alien abduction experience.6

Port Isaac and St. Teath lie some five miles apart, but the incidents in question are separated by more than three hundred years. That said, both episodes seem to occupy the same imaginative space. The filming of The Nightmare Man and the story of Anne Jefferies are cultural constellations that speak to each other across the centuries in strange, uncanny ways. They also open-up a version of Cornwall in which the vectors of place, culture and myth; the tangible and intangible co-ordinates of belief and experience, witness and fabrication ambiguously overlap. This is a space that exerts a strong pull on the imagination. Like the zone in Roadside Picnic (1971), the place operates according to its own rules.7 The Nightmare Man is a passport to this territory and buried somewhere in the story of Anne Jefferies is the secret of what you might find there.

III

Down in the village it’s the usual circus: the coffee shop that used to be a church, the gift shop that used to be a post office. You can’t move for local artists inspired by the landscape.

But there is this one guy who keeps a room booked out at the hotel all year round. He comes up here from time to time and sets a canvas by the window. Blue and grey, that’s it. He gazes at the sea. Takes pictures. Studies it from his look out. The canvases come out mostly the same. Sheets of blue and grey. No tone, no shade, no attempt even to get the wave form.

His shop in the village carries gentle watercolours of fishing boats and beaches. His paintings of Padstow are quite popular.8 But the hotel paintings are not for sale. They’re part of a special project.

He’s looking for something. A system. The inner architecture of the sea.

Wave traces of offshore islands visible only in a certain light.

Compelled. Drawn.

Headlands is his retreat, he tells me. A retreat from what, exactly?

The room is big enough to pace. In circles. Walk a whirlpool into the floor.

IV

In late summer 2015, we headed to North Cornwall to experience the pull for ourselves and to gather evidence relating to these fictional and folkloric events. In attempting to map this psychic territory, our intention was not to discern the ‘facts’ but to instead develop a reading of the landscape.9 We wanted to generate an interpretation of the area and its markings; we wanted to measure its various phenomena and, if possible, we wanted to attempt some form of divination, perhaps an act of speculative contact with Jefferies or whatever intelligences sought to identify themselves using her name. Overall, we set out to find the fluid places, the doorways and borderlands at which the physical and imaginative geographies of St. Teath and Port Isaac begin to blur together. Cornwall is a beautiful and fascinating place to visit but it was into this otherworld, the shadow side of the county, that we wanted to calmly and adventurously go travelling.

The Cornish landscape did not disappoint. This was from the outset an unconventional project but we were not prepared for the range and intensity of the experiences we had during our field trip. A number things happened which we found difficult to explain and in some ways – which are, again, difficult to precisely define – we are not the same people who started out on the journey. Nevertheless, in the words of William S. Burroughs (a writer for whom nothing was true and thus everything was permitted), we have ‘been there and brought it back’: Headlands is the result of our investigation.10

V

Sometimes the cloud descends and covers up the headland. They used to be able to do this on cue. Now when it happens, it doesn’t feel like a bridge unfolding. It feels like the whole place is closer to the water. Not floating. Submerged. You wait for a shape to form. Vast, groaning. A great weight that can pass unnoticed.

Out there on the perimeter there are planets we’ve not yet detected. We live in their shadows mistaking the shade for the blanket of space. Floating in our orbs we encounter system after system as intricate as the threads the bind the brain together.

If you want to know what outer space is like, take a boat and row out to sea.

Fitful sleep. Pulled out by the drone of shipping lanes.

Look around again: bed, desk, cupboard, lamp. Staring at the rose wallpaper. A window that holds the pressure of the water and beyond that, arrows.

The Headlands Hotel is derelict now.

Tomorrow I will leave this room and travel inland to a village called St. Teath.

IV

Unconventional projects call for unconventional methods of dissemination. Headlands has taken a variety of forms since its inception. The first was an exhibition of artefacts held at the Faculty of English, University of Cambridge in June 2016. This collection of texts, images and magical objects was intended as an essay by way of artefacts, an initial dispatch from the zone.11 In October 2016, we presented Headlands as a work of expanded cinema at a subterranean location close to the university. Using sound recordings and video footage gathered during the investigation and with the assistance of some close colleagues we presented our findings to the public.12 This immersive ‘experimental lecture’ – part screening, part performance – attempted to deliver the information we had generated but it also sought to reflect the nature of the events we had experienced. As such it was associative, impressionistic and deliberatively speculative: the tools of the academic re-calibrated to talk about something other.13

We are now preparing Headlands for release as an audio recording with an accompanying book of texts and images. The recording combines the text of the lecture with field recordings and other ambient material pertaining to the investigation. It is intended as an immersive record of our time in the zone. The book contains a complete, annotated version of lecture script alongside an extensive essay outlining our aims in undertaking the investigation as well as further contextual material connected to The Nightmare Man and the life of Anne Jefferies. The book closes with a conversation in which we reflect on our work with the project. Stills from the video material used in the performance and images of the objects we included in the original exhibition appear throughout. As a book, Headlands thus documents our various outputs whilst also taking the project one step further. It is an exhibition catalogue, a transcript of both the live show and the audio recording as well as a supplement that includes information and commentary not present in any of the project’s previous incarnations.

Taken as a whole, Headlands is a work of both fiction and fact. It is not clear to us whether we undertook a fictional journey to a factual place or a factual journey to a fictional place. The difference between inner space and outer space was somewhat indistinct for much of the investigation. We went somewhere and came back with something. That much we are sure of. We have compiled Headlands and worked through its prior versions in order to map our journey retrospectively. What we have collated is a set of footprints. Headlands is an afterimage on the lens; a message on the answerphone; the hidden channel between the stations.

*

Headlands will be released later this year on the record label Eighth Climate.

–

1 – J.G. Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition (1969), 82.

2 – The Headlands Hotel stands on an elevation between Port Gaverne and Port Isaac, part of the Parish of St. Endellion on the North Cornwall coast. The structure commands panoramic views of Port Isaac to the west. Transformed from a Victorian residential property into an 11-bedroom hotel over three levels, the business closed towards the end of 2009. Before this it had been used as one of the many locations in Doc Martin, a long-running ITV television serial filmed in Port Isaac. After its closure, the hotel fell into dereliction. A planning application was submitted to Cornwall Council in 2015 outlining a plan of demolition, conversion and renewed operation as a 14-room hotel. Other calls were made to turn the structure into private flats. Given the nature of Cornwall’s tourist industry, environmental importance and existing debates regarding its housing economy, both ideas attracted support and criticism. In the meantime, the remaining structure attracted the inevitable attention of ‘urban explorers’, see: www.youtube.com/watch?v=fIibkKUFH3c.

3 – We took extensive notes during our time in Cornwall. These italicised extracts carry some of the same tone but are not transcriptions of the original screeds. There is a psychic and temporal distance between the scenes of writing. Memories are hazy when it comes to the form, format and subject matter of the original texts. Their current location is unknown. It is possible that they were thrown to the sea. Regardless, they took the form of drafts for a short story. Something to do with measuring the sea and predicting its wave forms. Or something. We recall that one particularly uncomfortable morning on Castle Head (an outcrop from where Port Isaac can be seen), yielded a series of notes about a floating bier.

4 – The Nightmare Manwas adapted for television by Robert Holmes, a renowned script writer and editor who was best known for his work on Doctor Whobetween 1968 and 1986. The four-part series was directed by Douglas Camfield and shot on location in Port Isaac between 12 January and 6 February 1981. It was broadcast later that year across four weeks in May. Author David Wiltshire had previously published The Homosaur(1978) another science fiction novel about an archeological discovery. According to Andrew Pixley, ‘Vodyanoi’ “- or Wodjanoj, the Russian for “watery” – was a creature from mythology, a male water spirit […] that lived in a whirlpool of sunken ships”. See Pixley, The Nightmare Man: Viewing Notes(2005), 2-11.

5 – Moses Pitt was a printer and bookseller who was born in St. Teath in 1639. He was known for his Atlas of the world, a publication supported by the Royal Society. Details pertaining to Pitt’s letter can be found here: http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/prwe/prwe340.htm.

6 – Jenny Randles discusses the case in her Little Giant Encyclopedia of UFOs(2000). For Chris Aubeck’s account see http://ufoupdateslist.com/2001/oct/m15-003.shtml. Classic UFO photographs feature witnesses pointing to where the entity has been. They emerge as lonely considerations of empty fields, quiet roads and in-between spaces. St. Teath suits this unconscious aesthetic perfectly. The village has a heavy stillness and an odd sense of quiet which invites the present perfect tense: it is not quite a case of ‘nothing happens’, but more a matter of something having ‘just happened’.

7 – Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s science fiction novel Roadside Picnic (1971) deals with the aftermath of an extraterrestrial ‘Visitation’. This event has resulted in the emergence of global, supra-phenomenal ‘zones’. Littered with anomalous artefacts and rumored to contain a wish-granting sphere, the zones are navigated by ‘Stalkers’. The novel formed the basis of Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (1979).

8 – (James Riley): ‘To confess, I’ve never quite seen the appeal of Padstow. There’s nothing wrong with it, I just get a gloomy feeling every time I go there. A pressure comes over me and I can feel my mood slipping away from me like water down a drain. Maybe it’s the ‘ghoul’ that T.C. Lethbridge felt when collecting seaweed at Ladram Bay in Devon. The depression that descended on him was attributed to various kinds of atmospheric pressure as well as forces that require more of an esoteric explanation. Colin Wilson provides a wonderful commentary on this encounter in his bookMysteries(1978). We have been privy to other accounts of this nature which leads us to speculate that zones of this type may well be proliferate, punctuating the coastline.’

9 – According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘reading, (n)’ carries a number of different interpretations: ‘The action of perusing written or printed matter; literary knowledge or scholarship. A social or public entertainment at which the audience listens to a reader. The act of interpreting or expounding a dream, sign, etc., sometimes for the purpose of divination; The inspection of objects such as tea leaves, cards, the palm of the hand, etc., for the purposes of divination or fortune-telling; The measurement indicated by a graduated instrument; an instance of taking or noting such a measurement. The copying or extraction of data from an electronic medium or device; the transfer of data into something.’

10 – William Burroughs often spoke of his writing as an act of ‘psychic’ map-making. This is evident in some of his earliest works such as The Yage Letters (1963) written with Allen Ginsberg, as well as his final ‘Red Night’ trilogy that consisted of Cities of the Red Night (1981), Place of the Dead Roads (1983) and The Western Lands (1987).

11 – See https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/news/archives/2056.

12 – We were grateful to have the enthusiastic support and participation of Jo Brook and Andy Sharp.

13 – See http://www.crassh.cam.ac.uk/blog/post/crassh-and-the-alchemical-landscape-at-the-festival-of-ideas. A video trailer for the event can be found here: https://vimeo.com/183114048.