Graeme Cole proposes a curriculum for a new filmmaking school which champions the amateur and the absurdist over the professional.

Action

Action: the most celebrated word in filmmaking. Delicate filmmakers may prefer the term ‘movement.’

What are you doing now? I’m writing a manual, and developing a filmmaking academy. The manual is the working document of the academy. The academy is called Unfound Peoples Videotechnic (www.unfound.video).

A manual. A doing book. Action.

Process: another doing word that doubles (triples?) as an adjective and a genre. Try shouting this one at your actors! “Lights. Camera. PRO-CESS.” Could be good.

Because?

What are you doing? Co ty robisz?

I am asked what I’m doing twenty times a day. It is our two-year-old’s favourite question. It’s a good question, asked in a range of tones from “curious” to “aggressive”.

Another favourite (and toddler classic) is: “because..?”

“Because…?” can be applied to any story or explanation and each sub-explanation. After every answer, another ‘because?’ probes deeper into the Russian Doll, the infinite stack of cosmic turtles.

The two-year-old has hit on a classic systems design technique: Sakichi Toyoda’s Five Whys. However, the toddler’s system is more rigorous. Mercurial, tireless, merciless.

Sometimes, with a worrying concern for traditional narrative, she will swap in a

-

- “but…?”

- “and then…?”

- “so that’s why…?”

regardless of whether the story begs it. Regardless of whether the explanation can even fit a new layer of cause and effect.

These questions represent very vertical thinking.

No horizontal “meanwhile…?” No ambient anecdote. No novel set in a single moment, a la Perec.

What are you doing?

Because?

How should/could an absurdist film academy operate? What would help you, as an artist, filmmaker, movie enthusiast, accidental reader?

Here is a sample of working tenets that have endured at the Unfound Peoples Videotechnic from the beginning:

The instruction should be so close to being useable that it aches.

And yet, every concept has to have a practical application, away from the classroom or the computer. A “meat test.”

Indeed, the instruction should be in concrete terms. Things you can see, hear, do. Theory embodied in demonstration (or at least illustration).

The reading list and filmography should acknowledge not just canon and canon-resistant filmmakers but those who never quite existed at all.

No Dostoyevsky. No Tarkovsky. No boy’s toys.

Mistakes. Situations. Breakfast.

We should acknowledge that:

-

- Most film viewings don’t take place in the cinema

- But the cinema environment is precious and endangered

- Tiny screens are exciting

- Your movie will most frequently be seen in a transferred and/or damaged iteration of the copies you distributed.

The institution should dismantle itself and make its component parts available as tools. Then re-constitute itself neatly by the end of class. (Still working on this one).

The school, I wrote, “will be as transparent as possible within the boundaries of dignity, vanity and insecurity.”

Looking back, I would add an Oxford comma after “vanity”.

Now

Amateur: to love. The amateur filmmaker can only fail if they fail to love.

Sounds good. But who/what should you love? Does getting paid buy off your affections? How not to get paid?

Right now, I’m developing an ‘essay film’ for the Unfound Peoples Videotechnic at the Visual Narratives Laboratory of the Łódź Film School.

A film school within a film school within a film school. A not-quite infinite stack.

The essay film will complement a module at the Unfound Peoples Videotechnic. The module is called Advanced Amateury (How to be better at being worse: clumsy loving in the age of competent content).

Here are some notes from my preparations:

The amateur tends to be identified by what they aren’t. Not what they are. Or what they don’t have. Not what they have.

The amateur may be accused of being an amateur because they are not:

-

- Trained, or

- Professional, or

- Profitable, for instance.

Why might an amateur choose or accept these limitations?

Here are some reasons you might choose to be amateur:

-

- To disrupt ingrained ways of doing things.

- To communicate in new ways or unfashionable old ways.

- To maximize joy and minimize stress.

- To allow for possibilities that professionalism excludes.

- For lower economic risk.

The essay film will utilize several categories of clip. These categories include:

-

- Films about amateurs.

- Artful mistakes.

- Evocative flaws.

Amateurism is often defined as a lack of training, employment, or profit. But amateur means ‘to love.’ The amateur cannot lack unless they lack love.

The essay film will be constructed with footage from the archive of an industrial film studio, Wytwórnia Filmów Oświatowych. Illustrating amateurism with the work of filmmakers defined by their professionalism! The course leaders worried I would struggle to find mistakes. But it’s all a mistake, isn’t it?

Anyway, I will supply my own errors. Scupper. Put aside the little I’ve learned while preparing video lectures for Peter Treherne’s Slow Film Festival. Try some new techniques and tinker with affection.

Not to introduce deliberate mistakes, but to soften the ground.

Vertical

The radical “but?”

The interrogative “and then?”

What can these questions offer our narratives and our processes as filmmakers?

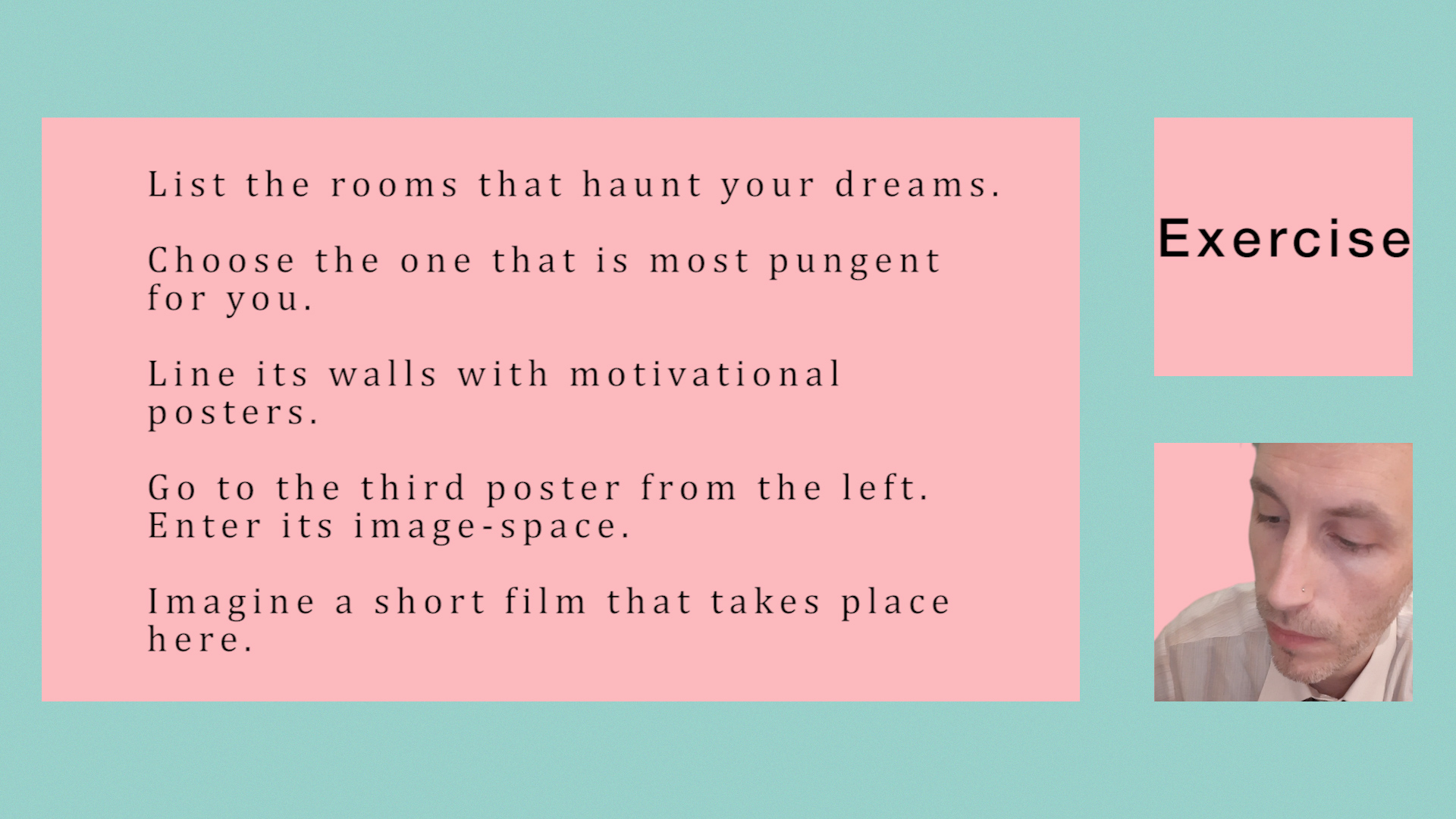

Imagine a super-pared-down set of Oblique Strategy prompt cards. Not for use when your creativity gets stuck, but when it’s going too smoothly. One thousand cards. Awkward but comforting to keep in your inside pocket.

Each has one of the following prompts:

-

- Because?

- But?

- And then?

- So that’s why…?

When you notice your work is going smoothly, choose a card. It is mandatory to answer it at that exact point in/on/through your work (writing your script, shooting a scene, midway through a stunt). And then another card. And another.

Down and down, turtle by turtle, until you’re stuck still again or you’re ready for a nap. Whichever happens first.

Action II

The final chapter of my newest, final movie, is titled: ‘Action’.

The movie is a ‘making of’, but its working title is ‘The Unmaking of Chaos’. Because my ‘making of’ follows a feature film crew’s attempts to de-assemble and reassemble the chaos of the/a human experience (through the feature’s narrative and in the very making of a film (the making of every film is an unmaking of chaos).)

Most of the movie follows the director and her two lead non-actors as they film a road movie across Bosnia and Montenegro.

‘Action’ is structured around two long takes:

The road movie crew is filming on a mountainside farm in low cloud outside Bijelo Polje. The first long take is a cow in a field slowly being enveloped by fog. We hear the crew preparing the next shot off-screen.

The crew then prepares seven times for seven takes of a subsequent shot. So, my second long take is actually multiple takes superimposed on each other. I stood still and videoed the road movie crew preparing their seven preparations. And then, I superimposed my takes on top of each other so that you see the preparation of their seven takes simultaneously.

The viewer of Unmaking sees seven preparations for the same shot all at once. The same crew members and actors drifting through the same frame, often with seven ‘ghosts’ of the same individuals superimposed at once. Noisy!

My seven takes of the crew’s seven preparations are synchronized not when they begin, but when they end. At the point when the director calls “Action!” in seven dimensions, all at once. She calls “Action!” seven times at once, and the Unmaking ends.

My ‘making of’ ends in the moment that life in the road movie begins, in seven dimensions, seven forgotten turtles desperately paddling out of sight down below. At least six of those dimensions won’t make the final cut.

It’s an emotional sequence. Seven ghost crews, each ghost one take older than the last. Iterating. Trying seven variations on a process to a pleasing action.

“Mush!”

The artforms I have most stubbornly pursued are writing, filmmaking, and something like expanded filmmaking. (Not expanded cinema – expanded presentation – but ‘expanded collective studio-being’).

Now, I’m writing a manual, and developing a filmmaking academy. The manual is the working document of the academy.

My memory is mush. Most of my thoughts are gone. The remains fester in Word files created and forgotten around particular projects or studies. Notebooks of reprocessed thoughts from lectures with Béla Tarr, Guy Maddin, Juliette Binoche. Speculative documents created for an abandoned history of a parallel cinema.

The manual is, in part, an effort to build some soft but solid ground. So at least the mush can form a neat puddle in the classroom.

The book won’t make we, the faculty, any more certain of our technique. Certainty of technique is not desirable. But it will at least propose a structure within which to test the technique. Discipline.

(Discipline is very nearly another one of ‘those’ multifunctional filmmaking words. However, it should only be used in place of ‘Action!’ for very particular scenes).

But the manual is also a doing book. It comes with directions for its own use and misuse.

The book’s ideas and definitions should remain open.

Impossible instructions that require digestion rather than completion. Exercises that can’t be realized and koans that beg to be filmed.

Filmmaking appears to be the most objective art but its surface nature lends itself to suggestion, misguidance, doubt. The book, like your movie, should be architectural: the words/walls are the headlines, but the space is the story.

Shrug

The artist Aleksandra Niemczyk created a logo for the school. The ‘shrugging filmmaker’ logo transforms the initials of the Unfound Peoples Videotechnic into a filmmaker standing at their tripod and shrugging.

Shrugging, even in a still icon, is an action. Doubt is an action, although certainty isn’t, but falling is.

The book ‘dives deep’ on filmmaker Francis Dove’s principles of Clunkyism. Clunkyism was Dove’s way of being “sarcastic about certainty.” Briefly, techniques include:

-

- Choosing flawed materials and tending to/accentuating their flaws

- Accentuating the true identities of the materials

- But sanding down their strengths

- Tactility

- Putting altogether too much faith in the audience’s suspension of disbelief

In this way, Dove intended to:

-

- Humanize the scientific

- Devalue human logic

- Dismiss any definitive reading of the text.

Action III

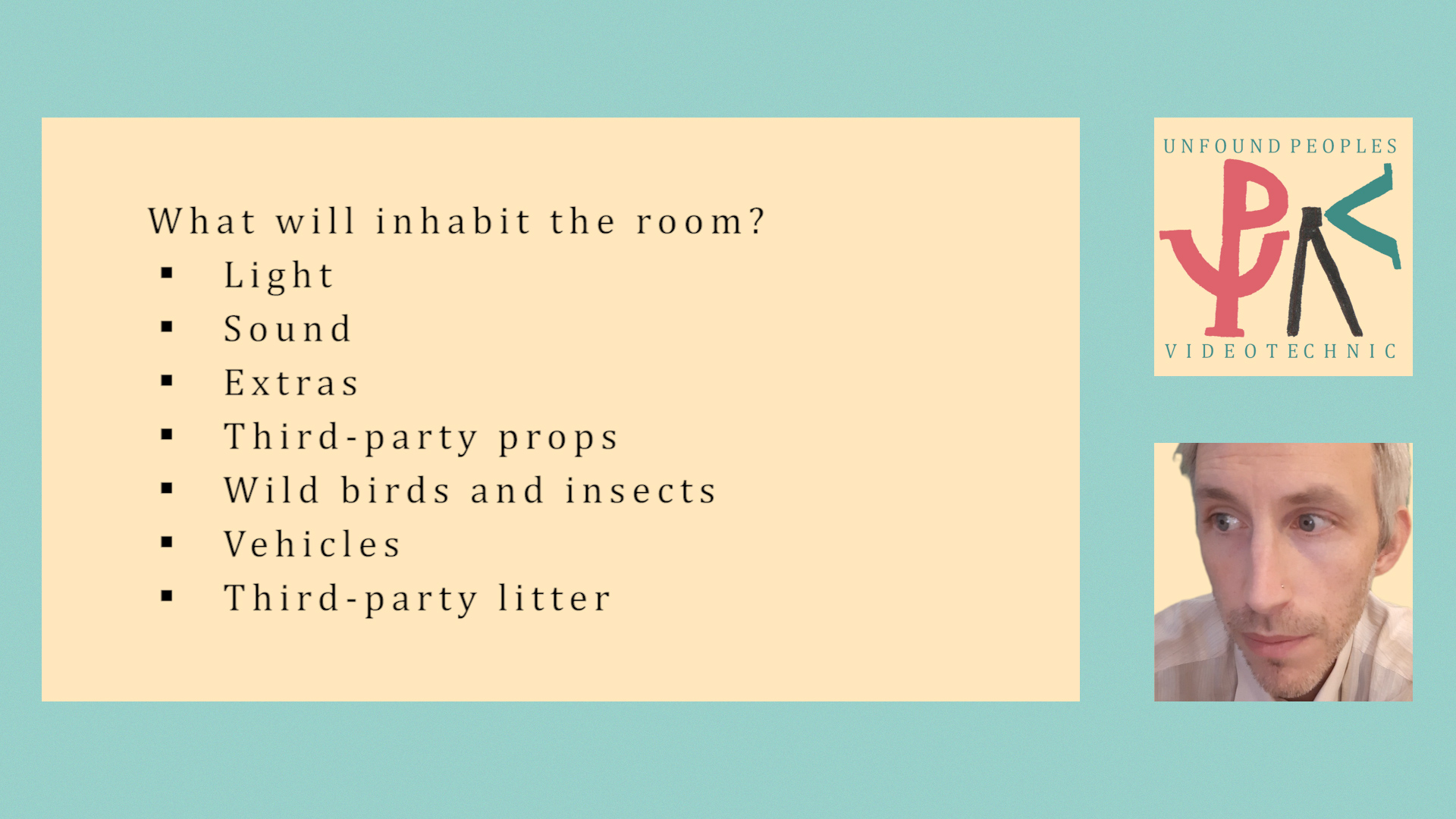

The UPV curriculum interrogates the material and aesthetic qualities of the actor. And explores the fastenings and sealants you need to stick the pieces together. The school values the sad enthusiasm of the boom operator. It considers the recording and exhibition formats to be a sequence of membranes or wrappers, between which are trapped the odours of your movie.

All this is to say that our school of thought and our school of making:

- Destabilize the connection between

- the finished movie and

- the world where the production takes place and

- the working mind of the viewer and

- the beyond place of mediaphysics

- Value, with healthy distrust, the physical universe

- Distrust, with sneaking admiration, the metaphysical

- Absolutely separate the physics of the movie diegesis from those of the ‘real world’ (i.e. the one with Tescos etc.) – redrafting them back into the movie law by law if needed

- Believe decay to be integral to every element and factor of a movie and its creation

- Are not so much anti-realistical as extra-realistical

- Consider filmmaking to be an act of design and question the daft assumptions ingrained into 100+ years of filmmaking design.

The book contains advice on fear. Encouragement for the dilettante. Exercises to strengthen your idiocy.

It is easy to make a film. Just press your camera’s “Go” button and shout, “Action!”

However, that Go-button has a lot to answer for. And don’t get me started on the word “Action”!

The best thing you can do is visit the website and sign up for the newsletter: www.unfound.video

Click for more articles in this issue: