Amy Cutler reflects upon the making of her film ‘All Her Beautiful Green Remains in Tears’ and untangles the complex ideologies within nature documentary.

Film notes on All Her Beautiful Green Remains in Tears (2018)

“The story of landscapes is both easy and hard to tell. Sometimes it relaxes readers into somnolence, making us think we are not learning anything new.”

– Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, 2017

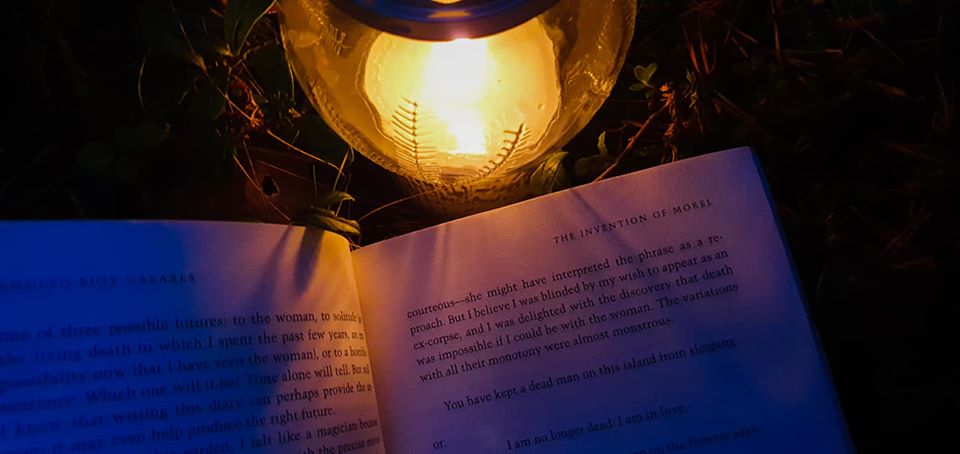

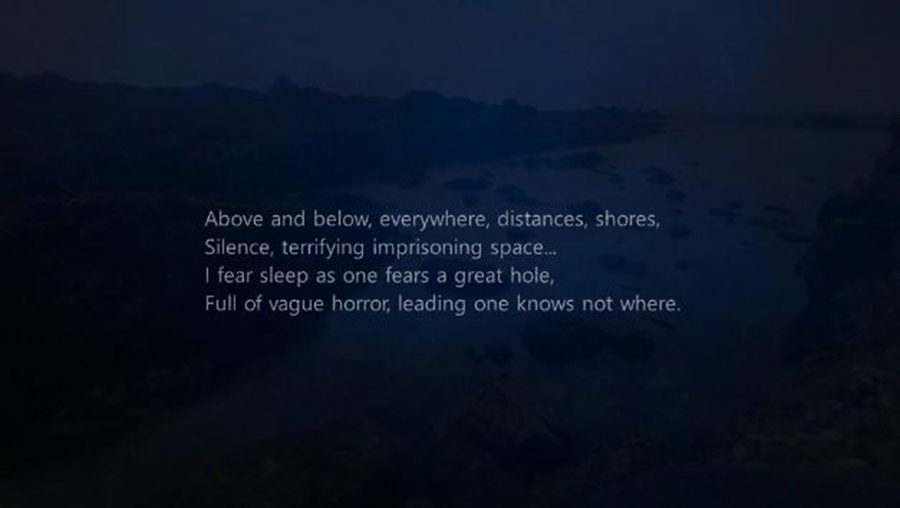

A nocturnal note written in one of Coleridge’s notebooks tries to describe the clairvoyance of landscape; i.e., experiences of landscape which go beyond normal sensory contact; even, landscapes that pass water. He noted that landscapes in a dream create real sensations, born into the world as umbilical “dream-terrors”, writing:

I have never of late years awaked, desiderio mingendi, but the preceding Dream had presented some water-landskip, Lake, River, Pond, or Splashes, Water-pits…

(Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Notebooks 1819-1826)

Coleridge’s dreamer is possessed by a “vast water-landscape” and experiences bodily pain through the strange colours and images of a dream; the landscape is an act of translation, or ‘the act of passing from the physiological into the somnial space’, between the bodily retention of water and the dream’s ‘generally stagnant but strongly aqueous landscape’ of moving images.1

In terms of moving images, a film of a landscape is another kind of translation of sensation; film, as a “science of light”, restores a landscape to us as a shadow, a reflection, a projection, a fable, or a remembered journey. These configurations play on the original “problem of landscape”; that it is a strange composite text, while also dangerously over-familiar. One of the problems of continuity in both visual editing and sound design is the association it builds between landscapes and matter-of-factness, assenting to the easy legibility of cliché. What we need is not more documents of landscape-as-articulated-fact, but instead, new “avant docs” of landscape – diagnosing the ways in which we make some landscape readings more legible than others, from the complexity of assemblages of government reduced to a single border, to the mobile, transformational ecological relationships hidden or reduced in the Homogenocene (Suckling, 2015) to land definitions focussing on extractive resources.

Perhaps even more than others, a “public” film text – like a found footage or archival film – rehearses these rubrics; the ways in which nature and environment exist in our discursive lives, and that we train ourselves to see them in certain ways. Between the geo-grapher (literally, land-writer or land-drawer) and the film-maker, the telling of stories of landscape requires all of our learning practices. So does the undoing of these stories.

My own films often concern stagnant landscapes, mired between the reflective and the immersive, or mental geographies, mixing dreams, novels, projections, visions, flash-backs, vigils, and walk-throughs (as in my most recent site specific film residency, over winter, on the uninhabited Finnish fortress island of Örö). One of the things I am invested in in my work, both in collaborations and in solo works, is a return to forms of “public” film, like the nature documentary – as an audiovisual training for the modern world; a suspension of disbelief, and a relentless green-screening, as backdrop to the proposed scientific authority. How can we work to restore the eerie in this green-screen landscape of nature documentary? – and by eerie, I mean the part where our narratives and ways of knowing fail; where the legibility of the environment accepts a gap or pause.

In particular, I follow the Iranian philosopher Negarestani’s use of the metaphor of a “plot of land”, as well as a “plot-hole”, in Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials. Can we, after Negarestani, find ways of becoming-vermin in these pedagogies – learning new ways to “plot holes instead of the wholesome narratives that cover them up”?

The story of landscape seems very simple. Just then you realise you have been sleepwalking.

As a film-maker and geographer, my work concerns bad framings of landscape; “commonplaces about common places”, or those received ideas and power systems we seem to sleepwalk through. Reading the landscape – the phrase around which the new cultural geography has organised itself – also means re-reading the landscape; de-coding its riddle. In fact, the verb “read”, in its earliest Anglo-Saxon form, ræd, means both to solve, but equally to pose, a riddle, as the late Nicholas Howe observed in Writing the Map of Anglo-Saxon England. Landscape is less a discipline than a metaphor for the ways we build our world view – so the stakes of this riddled world, and its modes of multiple authorship (and species-ship), are high.

I am interested in the problems of landscape, and nature, as a subterfuge or cover operation for a number of other undisclosed forces. Both geography and film-making give us particular tools to understand these forces, and the ways in which landscapes haunt us, but we also simultaneously haunt our landscapes – with laws, cartographies, histories, and invisible elements, from lethal contaminates to state power. Whenever we witness a territorial mapping of particular forms of narrative and voice, it is important to ask – which versions of landscape are being empowered, and which dis-empowered?

Landscape, like the techniques and expectations of film-making itself, is an always already inhabited view. All the landscapes we experience are constructed to some extent, and a film might show exactly how precarious these constructions can be – a set of habits, mirages, versions/visions, and our own training in various kinds of landscape vernaculars. The “taken-for-granted” concepts of environment by which we live rely on the fact that we are all highly trained – as audiovisual consumers, and as experiencers of landscapes, horizons, and broadcasts. Geographies which go beyond passive forms of reception of landscape are those which make visible (or even deliberately trespass against) our unconscious rules for construing, and judging, topography: say, the phobia of wetlands and “untamed” landscapes, or the expected scale we use when looking at certain phenomena – a forest, a fungus, a body, a coastline, a national border, a long-range cyclone seen via televised prediction models.

Landscape in film draws on these forms of amateur training as much as on fields of expertise. We are all already experts in our rhetoric of landscape – living in the same ambient collective mindspace which requires telling landscape “as it is”, which really means, navigated according to the same white lies of cartography, continuity, framing, the temporalities of video, technologies of vision, the picturesque, land ownership, legal definitions/classification, etc. Rhetorical and visual emphasis on seamlessness can mask the uncanniness of these agreed, pre-designated, never quite perfect techniques. The seeming trustworthiness of “landscape, noun, a unit of land large enough to be of telluric significance” hides its own history and continuity errors as different forms of an agreed understanding – as landskip, or as landschaft – with its strained relation to morphology, making/scaping, and the scenery of painting traditions.

In film and film editing, the same range of problems arise with a landscape approach, drawing on the disparate records which make up a social collage of a place, or a time, or a memory; the balance of collective forms, or oppressive erasures; the inherent difficulties of film as an accounting of an environment via certain patterns and filters of human and technological witness, from the monologue or voice, to the rectangular-eye view of the modern cinema screen (compared in film studies to anything ranging from a car window to a display aquarium). In this issue of MIA the filmmakers, individually and collectively, explore ways of tripping up some of these normal way-marking habits in moving images – offering alternative travelogues, in which the landscapes are obstructive, tactile, radicalised, or dreamed; either way, not as reliable as we seem to think they are.

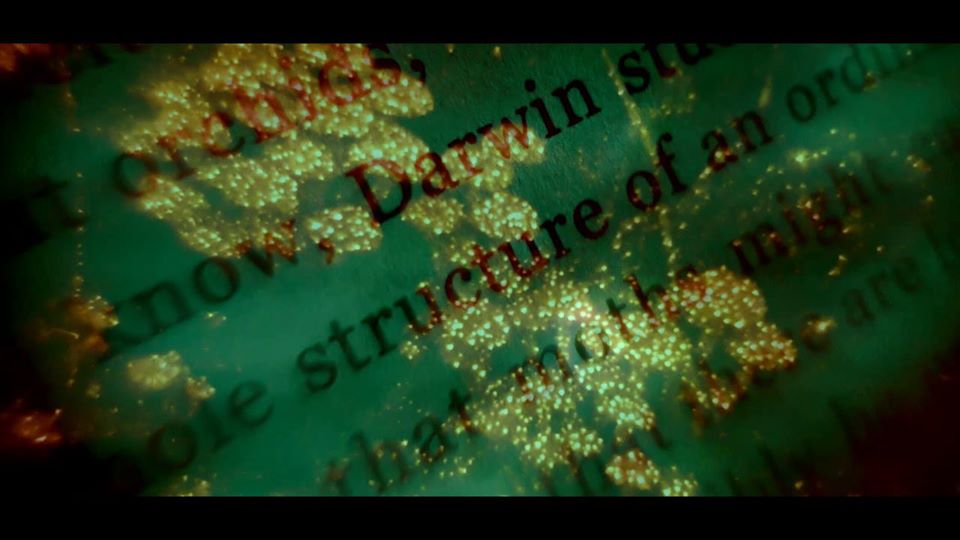

Returning to the making of my film All Her Beautiful Green Remains in Tears (2018) while in 2020’s Covid-19 lock-down has a strange timeliness. This film was a first prototype for a hacking of nature documentary’s “stock footage” powers; its pedagogies of the “birds and the bees”, and its ideologies of nature as a domestic – and domesticating – broadcast. In essence, this is a film using source footage drawn from our classic “mindscape” of nature (the nature documentary genre; an environment so familiar we could each redraw it with our eyes closed), but re-writing it with the help of an artificial intelligence.

The film itself consists of re-purposed footage from Walt Disney’s Nature’s Half Acre (1951), with its parables about domesticated post-war suburbia: nest building, chick rearing, mother love, industrious insects, and a return to traditional gender roles. Coinciding with the move of nature documentary from bombastic cinematic releases (descended from hunting expeditions and colonial style museum dioramas) and exotic canyons and jungles to the new intimate frontier of television in the home, this 1951 release filmed in small meadows was the Disney company setting the template for the most powerful housewife-marketed visions of nature in twentieth and twenty-first century public television to come. My re-edited, re-scored version has a soundtrack by the musician Leafcutter John, who specialises in creating natural landscapes and ecologies from generated noise, often using DIY gadgets. Meanwhile, the new synthetic voice-over – replacing the paternalistic, judgemental tones of the original narrator, Winston Hibler – also focuses on romantic anthropomorphism. The difference is this narration has been generated by a neural network, having learned its existence entirely from reading the female protagonist voice in 14 million passages of romance novels.

Using image recognition and television closed captioning to identify what it sees, and its training on romance novels to generate a voice to try to narrate this, it tells an entirely different story of the “birds and the bees” of nature documentary in the close-to-home American meadows and backwoods: one of female desire, trauma, masochism, and emotional fantasy. It revisits the sexist betrothals and suburban values of the traditional disembodied male scientific or “god-perspective” narration – including its focus on the bird’s nest as nuclear household, and its patronising DisneyNature tales of family dynasties and “Mother Nature”. Here, the synthetic, post-human voice – sourced not from any one individual perspective, but from mass media archives of closed captioning – speaks not with the trusted, BBC-sanctioned expressions of child-like scientific wonder, like that renowned person-as-institution, David Attenborough, but in fact with a very different kind of wonder. “She” speaks, passionately, of consuming or being consumed; of touching and being touched; of the tactile, imagined surfaces of “her” own body, or of the earth “covered in goosebumps”.

Finding herself in a nature documentary, the unnamed narrator scans and enumerates her environment, attempting to itemise and understand it. As opposed to the traditional nature documentary voice-over, which ventriloquises the landscape according to its own powers – the ‘disembodying tricks’ (Kerridge, 1999) and technological clairvoyance with which it can, invulnerably, penetrate any swarm, climb the highest mountains, confidently see through submarine darkness, and ultimately, tell us its all-knowing scientific picture of a world that makes sense –, the narrator of All Her Beautiful Green Remains in Tears more often seems lost, confused, mistaken over the colour of the sky, or struggling to surmount her own emotions.

Her observations are born of a series of empathetic confusions, in which no hard line exists between observer and observed, or the different environments, selves, flora, fauna and biota. “She” looks at a series of Georgia O’Keeffe style flowers opening, and in response immediately becomes a being now knowing itself to be opening, with its most intimate parts on display. “She” is moved to cry or gasp more than she is to explain, seeming to be caught in the landscape of a dream vision, tormented with doubt, hallucinating, gaslit. Most of all, her narration of the woods around “her” home takes place always at night, even the bright bees, skies, and sunny spring flowers – no matter the time of day in the footage, the narrator describes it in the shades of a perpetual midnight, and the sunniest of spring flowers are still mysterious night visitors (invited or uninvited). Even when she does eventually “see” the blue of daylight, it is when describing the sky as a blue unmade bed with crumpled sheets. This is because the voice is trained on romance novels – that masochistic genre aimed most of all at a demographic of (housebound) female readers, with the largest majority of the scenes in those books taking place in the middle of the night. The narrator seems to be constantly walking around her house restlessly at night, whether in a sense of virtuality and aerial projection, or just the restlessness of her spirit causing her to pace through the woods and meadows when she should be sleeping. Like the experience of Coleridge’s dreamer, the landscape here is felt as a sensation which is somewhere between the physiological and the somnial space – landscape as a confused, painful dream, with all the colours wrong.

In the making of the film, I felt I dealt constantly with the thinness of the line between the generic and the surprising. The film follows the same patterns as two ultra-derivative genres – the romance novel, and the nature documentary – but the machine learning element makes it more rather than less idiosyncratic; the dissonance between the interpretations of image and voice exposes how habitual our scripts usually are. Where a human being would follow the rules – we are data-regurgitating organisms, following the rhetoric of landscape, nature, and romance – this narrator is often given to mistake, or break the rules, or blindly follow them to a point which brings them more visibly to our attention. In spite of the fact that “she” can only speak with vocabularies already-uttered – the common denominators of captioning keywords and the novels – she is in fact far more individualistic than the narrators to which we are accustomed, who are presented as individuals but actually speak in chorus, personifying an institution’s inarguable “reasonableness” (Graham Huggan’s work on David Attenborough and the BBC, in his book Nature’s Saviours, is particularly incisive).

Included here in this issue of MIA is the “script” co-written with my machine learning collaborator. Some of “her” substitutions, in describing the landscape, are particularly telling – both those included in the final film, and those in the thousands of pages which were generated as part of the process of the making of the film. Having split the original footage into stills every 0.1 seconds, and fed these into the machine learning programme (on a programme run by Anna Ridler, who also trained the synthetic speaking voice on recordings of her own voice – speaking as “Anna 2.0”), I found that the most time-consuming part of the process was reading “her” outputs – a sheer, overwhelming barrage of text and data generated by every micro-second of footage. In the process of working together, I then arranged and edited the new film according to what this machine learning collaborator seemed most interested in talking about, or talked about most revealingly. This necessary stage of collaboration – creating a film at the end stage of the project which became again comprehensible to a viewing audience, as well as most demonstrative of the findings of the larger process – allowed the film to set its own pace, moving between musical structures and moods, such as the early nesting stage, and the penultimate “blooming” section. Most of the insect footage was left on the cutting room floor, because the AI tended to not recognise insects (memorably, on seeing one insect, she described it as “a cake in the shape of an insect”).

In fact, this was part of her larger inability to see wildness as anything other than domestic, or domestic facsimiles of wildness. A larva becoming a chrysalis is described as “a small stuffed animal”. Technological and domestic filters such as these are always present. Because “she” learns her image recognition from closed captioning on television, the things she finds identifiable and visible reflect the bias of these channels, and the likely programmes, such as cooking shows, interior decorating, fashion, or other kinds of home-making; insects are nearly invisible to her, although she is interested in a caterpillar in a leaf, and later by the lustre of a cocoon, describing them in turn as “a surgical procedure taking place while the subject is covered with a green cloth”, and as the most beautiful garment of clothing she has ever seen. Strikingly consistent, compared to the certainty of the David Attenborough style voice, is her incredulity or even disbelief at the sight of birds. Over and over, she describes a bird as a plate with the pattern of a bird upon it, or as a haunted photograph of a paper bird. In fact, she never fully overcomes her suspicions about the reality of birds.

In the script generated by the neural network, eternally night-walking, there are also occasional hints at a traumatised consciousness; watching a woodpecker drumming on a tree trunk, “she” is prompted to leer over it: “I loved that delicate bark – it was the only source of fresh tears”. The commentary in the film script remains cryptic, as well as cryptically unhappy or joyful, laconically shocking, and sometimes even desiring. The desire is one of the most noticeable aspects of the film; like the plot-hole which “ethics” opens up in the plot of “morality”, we can see here desire which, queerly, strangely, opens as a plot-hole in the nature documentary’s closed-down plots, which code out married love, family, and the responsible middle class white household, against threatening predators and femme fatales. We can see here libidinal energies and empathies beyond the repronormative and heteronormative order of this genre’s “tyranny of formula” (Bouse, 2011); perhaps closer to that concept of desire as diverse energies, which LaFleur described in The Natural History of Sexuality in Early America (2018) as ‘the drive with the potential to undo the human itself’.

Perhaps most intriguing, to me, is the neural network’s dialogue with the suburban values of the original public film – which, after all, saw the intimate transmissions of nature mostly as a “teaching moment”. Nature documentary is the ultimate rom-com or Aesop’s fable; in this 1951 one in particular, we saw a postwar advocation of mother love, notably in the fierce condemnation of the cow-bird, North America’s most common brood parasite. The original narrator, Winston Hibler (who looks and sounds exactly how you might expect from the name ‘Winston’), consciously expounds on the “good” stay-at-home models in the natural world, within the context of post-war American women starting to make their way at this time in newfound independent careers away from home. But, he declares, “In nature’s half acre, mother love is expressed in patience and devotion. Be it fair weather or foul, mother always stands by”. He is aghast at the behaviour of the cow-bird, no matter that her techniques are equally natural to her and her ilk: “this heartless creature lays her eggs in another bird’s nest, and flies away never to return”.

The narrator of All Her Beautiful Green Remains in Tears, prompted by the very same sequences of bird’s nests and chick-feeding, also strays into a reverie on motherhood, and attempts to find metaphors for it in the natural world. Early nature documentary was forged on the private scenes of animals caught on camera usually either mothering or eating, and this machine learning narrator seems unable, in some ways, to now divide these two areas of life. (Is a mother a meal??) Her speculations about maternal experience show a consciousness partly understanding, and not questioning, the rules by which human sexualities and reproductions are explained according to “the birds and the bees”, but without understanding the additional rules of the social niceties of euphemism. She has an accidentally more startling take on the birds and the bees, speaking as if to herself: “I couldn’t help but think about what it would be like to have children, like a group of bees eating at an apple still on the tree.”. This sudden image of self sacrifice in motherhood – one of the examples of the policing of “labour” (in both senses) considered by contemporary feminists and writers on gestation practice, including Luce Irigaray in To Be Born (2017) and Sophie Lewis in Full Surrogacy Now (2019) – is perhaps most reminiscent of the striking line spoken by the narrator in Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment: “I was like a lump of food that my children chewed without stopping”. The neural network achieves a similar image, purely through her confusion, watching chicks being fed in a nest, about which part of the image is the speaking subject: is it the nest speaking? The placenta? The branch or the chicks? Is it all just one conjoined creature called motherhood?

As a project, this film speaks to the pitilessly patriarchal structures of nature documentary as a simultaneously public and private landscape. Nature documentary itself is an artifice offering up a memoir of “private life”, in the way it forges stories as biographies. In fact, from the first bio-discourses of cinematography – with devices given names like Bioskop, Biograph, and Vitaskope – there has been a focus on scoping the lives of “electric animals” in the shaping of modern nature, carrying over from a wider discourse of liveliness in scientific communication, and even of cinema as life science. From the courtship rituals of laboratory films like Huxley’s The Private Life of The Gannets (1934), and the progressive gender politics of Jean Painlevé’s The Love Life of the Octopus (1967), the nature documentary shapes our spectatorship as eavesdroppers on the intimate science of secret lives. Latter-day documentaries such as Life on Earth (1979), Trials of Life (1990), Life in Cold Blood (2008), Life (2009), and Life Story (2014), also remind us of the play inherent in the story of ‘life’ – as both a marker of the deeply private, uniquely held experience, and as a name for the widest of environmental processes. The nature documentary doubles these meanings into a personal and public life-writing of the Earth – a kind of surveillance of the clandestine encounters of both animal or biotic self, process, and world. This confusion of the multiple life-forms, life-writing, and life sciences of the nature documentary means the presentation of such pseudo-intimacies often hides a moral sleight of hand. There are the individual scales of private life (good bird mother/bad bird mother, animals as Hollywood drama-biopics, or soap-like “family dynasties”); these scales are then for all intents and purposes collapsed together with the level of the planetary scales of the survival of life on Earth itself, with this scale collapsing often used to generate empathy or the sense of risk. According to this structure, the common protagonist, an individual orphan animal battling against threats to its own (fuzzy and charismatic) survival, becomes every animal – a mediagenic Everyman, or canary in the coal mine, representing the wider fates of environmental health at toggling private/public/world scales.

A final point about the script included here in MIA is its ambivalence about tense. A classic twentieth century nature documentary follows a strictly ordered pattern. That pattern is an amulet against the darkness; a sign of love’s protections as the cycle is restored. Classically, this would be divine, seasonal, or symphonic – or in Nature’s Half Acre, all three: evolved from the city symphony films of the 1920s, the musical structure of nature documentary via its score suggests, ultimately, that whatever happens, the season of spring will ultimately arrive again, in God’s safe divine order of nature. But, however comforting the final pattern, this genre is still always told in an eternal nail-biting present; “this” orphan animal, fighting for its life right now. Although the films tend to be compiled from mixed footage of very different provenance, the key illusion is that we are spectators of current risk; life and death struggles and chases, right in front of our eyes. In fact, one of the most common words in nature documentary is “meanwhile”, evidencing the fact that much of the work of the script is designed to give a false sense of seamlessness, with an implied cascade of ecological connectivity – a sort of “ecology of the montage”, as it were. Individual problems are raised, a few tears are shed, and then we reach the symphonic resolution, with perhaps an afterword of hope, or worry, for the fresh new year or cycle.

This constant, anticipatory, beleaguered present seems even stranger when one considers that made-for-TV wildlife programmes largely take the form of compilations, assembling mixtures of new and virtually ageless and therefore endlessly recyclable stock footage from various sources, to survey a particular set of behaviours across species. The act of creating a “new” nature documentary is predominantly one relying on the rights to acquire or re-license footage. We have got accustomed to the temporal, spatial, and sonic anomalies of nature documentary which obscure the reality of the process, and scripts and scores which are designed to immerse us in a present landscape, while promoting certain emotions and responses – and remaining answerable to the narrator’s scientific assurance. We are, in fact, too fluent in nature documentary so we aren’t always aware of the dangerous logic of some of these grammars, which pass us by or escape our notice – while relying on our own, trained mental ability to connect the dots in this landscape, like the speaker in the Robert Duncan poem: ‘Often I am permitted to return to a meadow / as if it were a given property of the mind / that certain bounds hold against chaos’. As a film-maker, I often return to this idea of the connect-the-dots landscape, which relies on the film viewers to construct it each time.

Nature documentary is a distinctive media practice which is often overlooked by disciplines, critics, curators, and film programmers alike – due to various complaints: its non-auteur status; its decayed documentary ethics; its status as recyclable or stock footage; its production of “nature by rote”, or, as one critic complained on early releases of the Disney company’s True-Life Adventures series of nature documentaries, of “nature on the assembly line”. It is a genre which belongs to everyone and nobody; a no man’s land of film. This inheres not just in the output video itself – but in the media landscape which makes nature documentary what it is, defined by particular channels of control and spectatorship. This is not just to do with the conversion of the data of nature to fables of labour, morality and re-production relevant to human life-spans, but also the conversion of viewers into their willing state; emotional, seduced by danger, but ultimately unchallenging. The nature documentary, shaped by how it is transmitted and circulated, has become an entirely exhausted, but also somehow simultaneously entirely inexhaustible, genre; telling the stories of life and adaptation, while perhaps itself not always proving adaptable enough. But what does it mean to tell stories about a world which isn’t re-runnable, in a format and genre which essentially is? This genre is a form of film-making that will always travel “in formation” across our media, as Bill McKibben irritatedly observed in 1989’s The End of Nature:

‘Animals amble across the screen all night and day – I saw the same squad of marching flamingos twice during the day on different networks. (“They’re stupid”, said the handler on one of the programs. “It took me six months to get them to walk in formation.”)’

In other words, this is a genre about stupid animals, which treats us like stupid animals. The fact that the baby iguana escapes the pythons “this time”, as we watch with baited breath, and lives to fight and eat and nest another day as the cycle turns at the end of the show, might be colder comfort when we remember that the discrete parts of the footage making up the programme (not to mention the iguana itself!) are, likely, now well past their expiry date.

The narrator of All Her Beautiful Green Remains in Tears, however, does not live in real-time; or at least, not in the same gigantic ongoing strip of “real-time” landscape favoured by the genre of nature documentary. When she attempts to “be in” a landscape, she is still burdened by memory. She is identifying what she is watching in the springtime, autumnal and winter-time woods, using closed captioning keywords to see what the film chooses to flash intimate close-ups of, and then finding her own language for it by searching through her memories; remembering another spring or winter in an already written novel; flashing-back, or losing consciousness, or maybe beginning to dream. So, in this version, we’re seeing the seasons of a suburban American wood in the way that a machine sees them; we are looking at nature as a machine looks at it, which means, in this case, filters which are technical and domestic, but also retrospective – and I might add, hypnagogic (describing the hallucinatory logic of the space poised between wakefulness and sleep). While her experience of the landscape is unusually tactile for the genre – often touching, or stroking, or crying over, or somehow consuming, the creatures she describes – she is also given to the familiar post-dream confusion: is it something I felt, or dreamed, or really did I just see it on TV? “She” looks at a mountain, and then describes it as “a mountain on the Discovery Channel”. Throughout, the script shows a neural network generating a voice to tell us (or tell back to us, based on what humans have, overwhelmingly, said before her) about the birds and the bees – and the butterflies and flowers – of nature documentary’s buzzing meadow of consoling life, all seen through the eyes of a decaying romantic anthropomorphism: masochism, sexual violence, love, traumatic desire, a desperation for poorly conceived and surreal acts of home-making, and a permanent confusion between remembered and present landscapes.

Her inability to see without a technological prosthesis often means that she is assuming the man-made status of much of what she sees, as an aerial display or deliberate spectacle; bees are described as “spectacular balloons”; one bird spotted through branches becomes a plane, seen through a chain-link fence; a final sequence of fallen autumn leaves flashing downstream in a fast moving creek was chosen to showcase her insistence on describing these flashes of colour as a “remotely-controlled fireworks show”. Beyond this focus on landscape as man-made, or as a form of spectacle which she assumes to be humanly “intentional”, there is another form of domestication she analyses. That is, the use of wildness and non-human nature as itself part of the domesticating pedagogy, and language, of desire. Her slippages between characters, deaths, and tactile encounters play out, in surreal terms, some of the “normal” gestures of translation which perform these erotics: the use of dying flowers cut from their stalks as love gifts or adornments – a rose, or a perfume; beautification and ways of decorating oneself with flowers and make-up; the habit of naming women after flowers and flowers after women (Black-eyed Susans), etc. And of course the most recurrent innuendo she encounters, of a garden, or a lady tending to her own garden. Often, her surreal twists on the non-human learning of desire seems less obedient than the standard – a rawer articulation of what is inherent in this translated lesson, from Erasmus Darwin’s amatorial botanics, to what Adeline Rother has termed “Zoö-curiousity”.

Rather than exotic landscapes and canyons, this was a more intimate transmission, in 1951, of the seasons of an American meadow, beamed to households around the nation: nature becoming a household name, as it were. Nature documentary is always already an armchair story of déjà vu; safely generic. At the same time, a nature documentary is haunted by its own experimental potential as a re-write; whether we think of this in terms of Baudrillard’s “regime of the simulacrum”, Barthes’ “tautology of myth”, or Connor’s work on “re-writing wrong” and Williams-Wanquet’s on the politics of re-writing. Nature documentary is always a re-write. Aren’t you starting to feel, on some creeping level, that we have seen this before? A mother bird, somewhere, is feeding her chicks in a cedar tree in early spring, but as she dips her head it becomes noticeable that one chick in the nest, from its size and markings, is not recognisably of the same species as the others. Haven’t I, myself, lived this life before?

A landscape is a learned procedure. In my films, depictions of landscape often approach acts of reading. I see my films of this kind as annotations on landscapes – testing forms of legibility, adaptation, or “instructions for landscape”, and taking place in a series of landscapes, which are themselves also just a series of rehearsals for understanding landscape.

Most of all, I am interested in working on landscape as a literally “prescriptive”, or “pre-scripted”, form. This hybridisation of landscape and forms of reading has created films which I see as sharing particular methods and functions with the field-trip, the map, the science fiction novella, the prose-poem, and so on. Important to this is to remember that the geo-grapher, as a figure, is not unrelated to other forms of fabulist; from its earliest examples as a field of philosophical criticism and literary imagination (in Strabo’s Geographica) to contemporary articulations. I sometimes think about a poet’s memoir I once read, by Gillian Wigmore, author of Soft Geography, who recounts her childhood in Northern British Columbia. In the first chapter of this memoir she remembers her first foundational moment of realising she was a geographer, which was also her earliest memory of telling a lie to her parents – a lie about her environment.

Traditions of the geographer as an un-remarkably truthful, factual scientist are out of kilter anyway with our actual, strange, imaginative, and political ways of knowing the land. This comes back to the idea of the geographer as a pedagogue, but also as a peddler of illusions; some of my live film work in particular attempts to explore the earlier overlaps between the geographer and the projectionist or conjuror, and the conjoining of forms of spectatorship and the original navigation of landscape – as in my current series of events, Torchlight Cinema (2020-). Traditions of the geographer-observer and traditions of the dreamer-writer have also overlapped, as well as the geographer and the mad scientist: obsessive, seeing and following patterns where they may not be present. Often taking on the romantic anthropomorphism, or the pathetic fallacy, of nature (e.g., the dismal swamp), my films tend to be created “after” literature, or in the footsteps of existing writers, habits, and concepts. This is sometimes the deliberate conception of a work. Vigil for Örö (2020, in progress), for instance, filmed in winter in off-grid darkness on an uninhabited island of the Finnish archipelago, combines Romantic forms of travel isolation and the historical form of the Scandinavian and Celtic “sea-watch”, extinction narratives, nocturnal vigils (with a torch and a cemetery candle), and quadrat ecology and field laboratory techniques, to create the film’s forms of landscape research in-the-landscape, including two of the semi-protagonists, the ghost antler lichen and the rare Apollo moth. At other times, the pre-ordained understandings or writings of landscape and nature may only be there in hints, as one thread in a shifting celluloid dream or “video uncanny” of nature.

The approach of All Her Beautiful Green Remains in Tears therefore, in one way or another, threads through all my work – its familiar/unfamiliar landscapes, its disowned or multi-voiced/non-monologic narrators, its multi-species empathies, its glimpses of the birds and the bees turned strange. Nature documentary – like many other forms of landscape text – is all too normal, and it is a style in which we are dangerously fluent. Perhaps this normality is exactly what makes it an ideal tool to hack, in order to explore the strange new normals of life on earth. In a world where environmental dysfunctions are linked to narrative dysfunctions – the stories that have already failed us, and nature – we need surrealism because the world itself is surreal; and because of the ways in which nature documentary, no pun intended, has been naturalised.

One of my recurrent influences as a landscape film-maker is the radical French poet Francis Ponge. Ponge’s close-to-untranslatable work, La Fabrique du Pré (The Making of the Meadow), approaches landscape as intertext, constantly re-setting its fabrications and puns. The making of the meadow is, after all, the making of the making of the meadow – or so we piece apart from this diaristic, disharmonic re-scoring. A nature documentary, too, is a dangerously “unthought environment”, a key public landscape, which we have been given the permission to visit over and over. I am interested in simultaneously over-familiar and under-familiar geographies, with no one author, where what is needed in the narrative is not traditional continuity, but the opposite; from cataclysmic unnatural disasters, to the archival shifting of different forms of temporality, access, and voice.

I aim to open up the powerful media flow of the nature documentary template beyond its stock voices. How can we resist the nature documentary’s current conformity, in a time when we should be seeing a myriad of possibilities for nature-cultures and post-human natures? Can we hack these texts and histories to go beyond the “oh-so-human-lenses” (Parikka, 2010) of the conventional form, so it can live up to its role as cutting edge science communication tool and collaborative technology – and its responsibilities to diverse multi-species encounters, animals, environments, and audiences? How is the normative sense of documentary itself already deranged – aesthetically and formally – by our mutating climates and futures, and by extinction as an idea, which fractures any linear sense of time or story? And how can post-human tools allow us to break and experiment with the habits of its authority – to open up ruptures within it?

If our master narratives are unravelling in extinction (van Dooren, 2017), and our existing narrative frames must become climate-deranged (Ghosh, 2016), the nature documentary template is ideally suited to testing these ruptures. Working with machine learning in particular allows me to experiment with ways of doing research, and analyses of existing scripts, transcripts, media archives, and their ways of scripting the interactive borders of human, animal, and environmental events – in ways that are surprising and might tell us new things. Given the power these narrations have to inform and police our own intimacies, and to mediate future imaginings of survival on earth, how can we release new languages from this material? How can we read them against the grain of their own power systems? Can we open them up to new critical remits, hijacking their fables of love, labour, gender, environment, industry, order, ethics, time, species, emotion, and reproduction?

And thinking about this field of film work again, the nature documentaries, as I am locked in at home due to Covid-19, I now want to ask – how did they in the first place turn nature into, partly, a virtual extension of the home? The nature documentary as just another household appliance, if you will? This 1951 broadcast holds part of the answer. Against all of these questions, this canonical half acre of nature in cinema, depicted by the Disney company, feels as if it is sorely lacking in plot holes. But that is why we have returned to it. It was switched on in houses around the country, showing, modestly, no more and no less than the turning of the year in a meadow.

But the turning of the year in a meadow is something which always catches us off guard. This is because the sleepy meadow is also ‘an eternal pasture folded in all thought’, in the words of Duncan’s poem; a cyclical film landscape, a video already seen, a landscape already transmitted or sensed. Not just déjà vu, but perhaps even déjà rêvé; the return to us of a landscape, already dreamed.

–

Click for more articles in this issue: